I support free markets and economic freedom. But do all markets make society better off? The college cheating industry offers a challenge. An internet search quickly reveals the abundant assistance available.

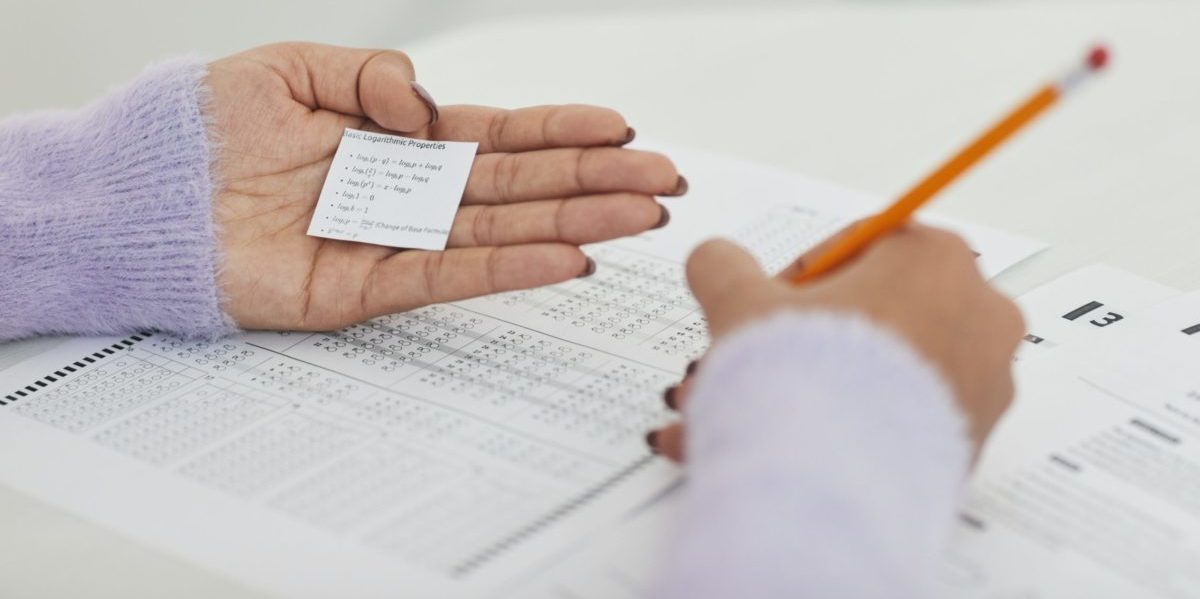

Companies and freelancers will write papers, even giving money-back guarantees. Uploading pictures of exam questions on a phone can get answers delivered. Entire classes and degree programs can be taken.

As a professor, I could easily moralize about cheating. But let’s consider the economics. A market for cheating exists because some college students are willing to pay for help. Specifically, they will pay enough to induce individuals capable of, for example, writing good term papers, to do so. The compensation must also offset any guilt about participating in misconduct.

Cheating clearly predates the internet, but now greatly enables this market. Students can easily connect with providers. Services can pay for ads to appear on internet searches. And paper writers use the internet to research topics quickly. Students demand custom-written papers because of plagiarism detection software. Software can now easily identify content lifted from the internet. Paper writing services routinely include plagiarism reports to assure customers of original content.

Further exploration of the supply and demand sides of the market raise concerns about higher education. On the supply side, many writers (seemingly) are graduates from colleges in the United States, Canada or Britain. (Poorly written papers are apparently common with the cheapest services.) Unemployed honors English grads offer many of the testimonials from cheating industry workers.

Some higher education critics argue that we have too many college graduates. Their evidence is often ambiguous. That the cheating industry can hire persons capable of researching and writing good papers on tight deadlines for about $10 per page speaks volumes about the job opportunities of at least some college grads.

On the demand side, the major question is why cheating works. Teachers warn cheaters that they only cheat themselves. This statement contains some truth. Cheating lets students complete an assignment or class without learning the material.

Does this truly help? Suppose someone cheats their way through truck driving school. How will they get and hold a job if they cannot put a truck into gear and drive it? Given this, why pay truck driving school tuition and then pay to cheat? The demands of jobs should limit the demand for cheating.

Cheating is more likely on classes unrelated to the jobs students will seek. College curricula feature required courses of little direct relevance to a major, like chemistry for future bankers. Shortening the bachelor’s degree by eliminating unrelated required courses should mitigate cheating.

College and graduate degree requirements are imposed by occupational licensing to reduce the number of practitioners. Occupational licensing is government permission to legally work in a field and has grown enormously in the United States.

Such degree requirements will be particularly susceptible to cheating; employers will not care if applicants lack irrelevant knowledge. What are the cheating industry’s consequences? The willingness of some to cheat requires professors and universities to incur costs to control and deter cheating.

The costs parallel the costs to businesses of shoplifting and employee theft. We could enjoy a higher standard of living if no one was willing to cheat (or steal). Cheating also diminishes the value of grades and degrees.

This is often described as unfair to students who study and earn their grades. But for the economy, cheating makes grades and degrees less effective in identifying strong students for employers. This is particularly costly when employers cannot quickly identify unqualified applicants, unlike in the truck driving case.

Cheating seemingly resembles other “victimless” crimes like illegal drug use. But this is not correct. The contract students have with colleges prohibits academic misconduct. Cheating involves contract violation, not merely consuming an unpopular product.

People will supply what others are willing to buy. But contracts are a foundation of economic freedom and enforcing contracts is a fundamental task of government. Protecting economic freedom does not require tolerating the cheating industry.

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.