The killing of 19 students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, has outraged Americans. The malfeasance of law enforcement during the tragedy is highly disturbing and demands reforms.

Police officers reportedly waited outside the classroom for over an hour. The commanding officer evaluated the situation as a “barricaded shooter,” not an “active shooter” calling for immediate entry.

A Border Patrol SWAT team finally entered and killed the assailant. Quicker action might have saved some victims. Economics counsels that there are no solutions in this world, only tradeoffs.

Ideally no one would ever try to kill children at a school. Unfortunately, evil exists. We can only manage, not eliminate, school shooting risk.

Let’s start with the frequency of school shootings. One frequently cited database tracks all school gun violence, like students getting in an argument and shots being fired. Such events differ enormously from Columbine, Newton or Uvalde.

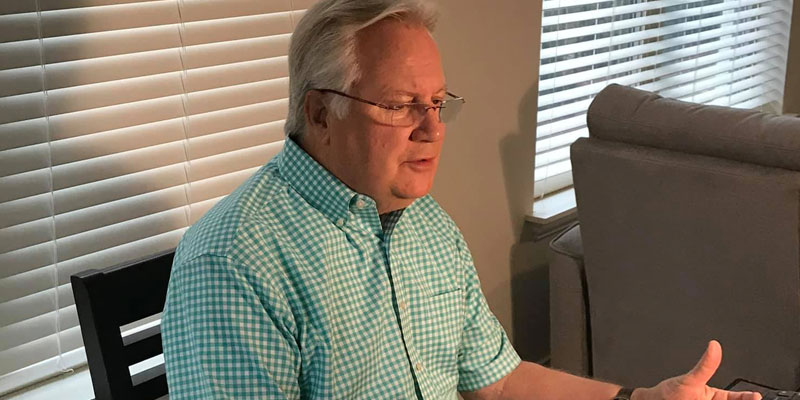

Bradley Thompson of Clemson University has compiled a list I will use. While school shootings seemingly happen all the time, Professor Thompson counts 14 events and 109 deaths since 1997.

Can we reduce this further, perhaps with better anger management? Over the past 25 years, over 100 million people have gone through high school (not all graduated). 16 individuals perpetrated the 14 shootings, or one out of 6 million students. The overwhelming majority of young people learn to control their anger.

Hardening schools is another possibility. America has 100,000 public and 30,000 private schools, so only one in 10,000 schools has experienced a mass shooting in 25 years. Many hardened schools will never face an armed intrusion. A teacher reportedly propped open the door the Robb Elementary shooter entered.

Locked doors will inconvenience teachers and students thousands of times for every intruder stopped. The infrequency of shootings challenges the human capacity for diligence.

The Uvalde assailant, like many school shooters, had no criminal record and no reported mental health incidents. Most shooters are not juvenile delinquents. I doubt psychologists can identify the one in six million in advance.

America has over 400 million guns, far more per capita than any other nation. Given all these guns, other countries’ gun control laws will work differently here. Even if we repeal the Second Amendment, Americans wishing to do evil will likely obtain guns. We likely must react to these rare events.

Experts stress the need for an immediate response by the first officers on the scene. Unfortunately, the dawdling at Uvalde was not unprecedented. The delay was 47 minutes at Columbine in 1997 and 58 minutes at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida in 2018.

After earlier shootings, experts recommended putting police officers in schools. An officer offers a chance to stop an incident before it starts. Not perfect protection: an officer will not always prevail against a well-armed assailant. Yet delaying a perpetrator might enable locking school doors and arrival of other officers.

Taxpayers paid for officers for schools. But at Douglas High the officer stayed safely in the school parking lot and Robb Elementary’s officer failed to engage the assailant. Taxpayers, I think, expected police officers to try to stop school shooters.

Can we expect better? Writing at Reason.com, J.D. Tuccile thinks not because, “officers are regular people working a unionized public-sector job” and have “no stake in the situation and families waiting at home.”

I think most police officers take their responsibility to “protect and serve” very seriously. Ours is a government of the people. Police officers ultimately work for us.

Detailed rules of engagement should be crafted by experts and not voters, but we set the broad parameters. If we want school shooters engaged immediately, we can and should insist on this.

We need a timely armed response to school shooters. Security guards at banks routinely engage bank robbers. If America’s police forces will not step up, we could cut police budgets and hire private security for our schools.

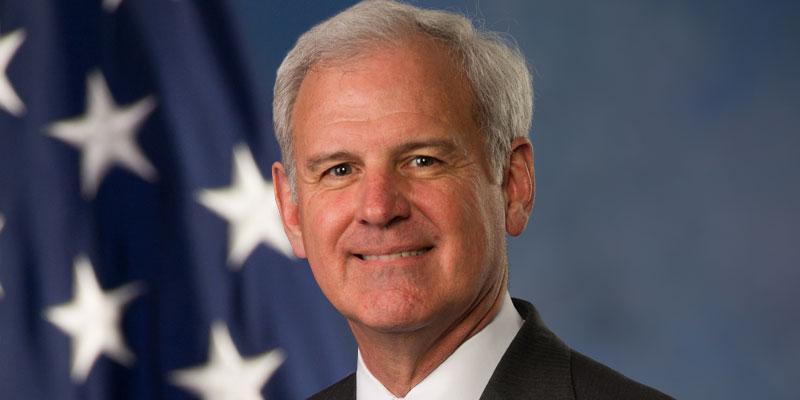

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.