The late Ronny Massey wasn’t the founding father of Citronelle High School football, nor that of Saraland, Leroy, Grissom or Thomasville, nor even of Tulane or Troy universities, but he was surely the uncle — and not the crazy one who let you smoke Camels or drink Budweiser or stay up all night doing God knows what when you slept over.

God knows, Massey’s house was built on doing things right, accountability and results. Back in the 1990s, at the height of his coaching career in Citronelle, Massey was an authoritarian without seeming like one. He was demanding and not despotic, fair and not flippant.

“If you did something wrong, he’d turn his head sideways and give you that look but he was never harsh or tried to embarrass a player,” said Saraland coach Jeff Kelly, a two-time All-State quarterback for Massey at Citronelle in 1995 and 1996. “When you’d screw up, he was always correcting and teaching.”

Massey demanded that his players earn everything they got and showed them they could aspire to something finer than being disrespectful, aimless and lazy, characteristics that the recalcitrant pop culture cartoon characters of the day — Bart Simpson, Beavis and Butthead and Eric Cartman — told Generation Y was acceptable, even preferable.

Massey countered the counterculture by being the North Star — always providing reliable guidance; his authority unquestioned, even eagerly accepted; his example never soiled with obscenities or heavy handedness or trivialities or ego. He had only a desire to teach.

The joy Massey took in football was evident to his players and made a difference in their performance.

“He was always excited to be on the practice field,” Kelly said. “He’d hit the practice field on the run and you couldn’t help but feed off that. He loved the game of football. I remember his practices being hard but I’d always see him smiling. I don’t remember seeing him when it looked like he was having a bad day.”

Massey’s record of 189-143-1 with six region championships and 16 playoff appearances at Thomasville, Citronelle and Grissom was good but not as good as those of his pupils — a lineage which is a testament to what and how he taught.

Great coaches, like great quarterbacks, make those around them better and he cultivated a thriving coaching tree that includes Kelly, current Citronelle coach Jason Rowell, current Leroy coach Jason Massey, Tulane’s Jon Sumrall and Western Michigan’s Lance Taylor. Combine their records and you have 338 wins, 159 losses, three state championships and two Sun Belt Conference championships. Sumrall was also Kentucky’s co-defensive coordinator in 2021, when the Wildcats were 10-3, leading to his first head coaching job at Troy.

“There are things I do daily that were influenced by coach Massey — the teaching part, the way he cared about his players that was bigger than the game,” Sumrall said. “The game is a great teacher on how to handle adversity, to grow as a man, to sacrifice. Ronny used the game to create better people and I have carried that over to my career.”

Massey knew how to run a team before he was a coach. At quarterback, he led Chatom High to back-to-back 9-0 seasons in 1968 and 1969. He played on Livingston University’s 1971 NAIA national championship team for Mickey Andrews, who later served as Bobby Bowden’s defensive coordinator at Florida State, and Massey quarterbacked the 1972 Tigers to the semifinals.

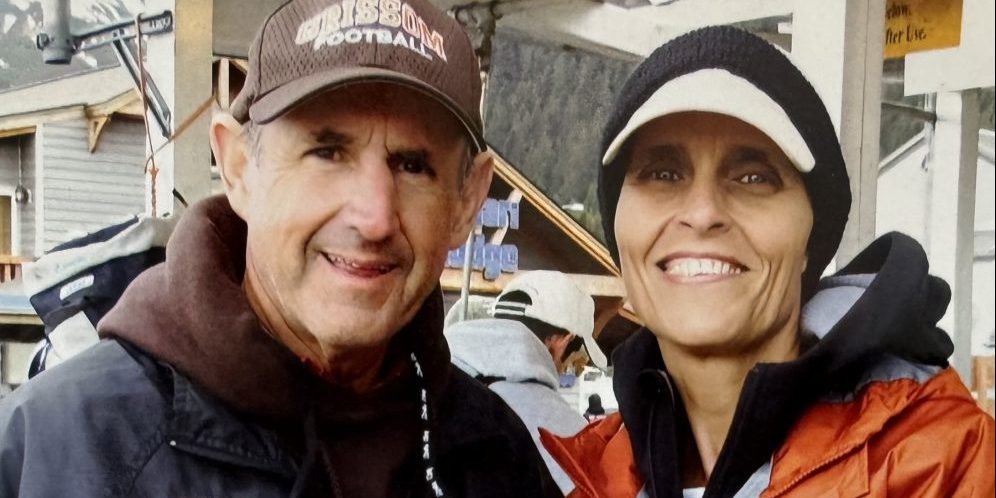

“Most of the best coaches are usually the ones who were college quarterbacks because they know how to lead,” said his wife, Helen, now 71, who is affectionately known as Ace, met her husband at Livingston, taught biology and served as his de facto assistant coach.

Kelly, one of those college quarterbacks, has long sought counsel from Mrs. Coach.

“She knows more about football and dealing with teams than most men I know,” he said. Ace is usually right, beginning with her choice for a husband, who never doubted what he would do with his life.

“Ronny said he knew from the time he was 5 years old that he wanted to be a head football coach,” Ace said.

Massey still holds the distinction of coaching the all-time best seasons at Citronelle (12-1 in 1991) and Grissom (12-2 in 2000) and made programs better wherever he went. He was 51-56 in 10 years at Grissom with the school’s only appearance in the semifinals; the team had just one winning season in the previous 10 years.

At Thomasville, he was 30-14 in four years after the team had gone 20-21-1 in the previous four seasons.

Besides numbers, perhaps a better way to define success is measuring the roots of a coach’s influence and Massey’s may never be fully calculated. He received a posthumous lifetime achievement award from the Alabama Football Coaches Association earlier this year and there is a scholarship named in his honor for college students who want to pursue coaching — but that, too, doesn’t fully capture what he means to so many, even 14 years after his death.

Massey had inspired Kelly to become a coach and a month before Massey died of cancer in August 2010, Kelly visited him at his Huntsville home and came away with some of the best advice he ever got, which had nothing to do with X’s and O’s.

“He made a comment I’ll never forget,” Kelly said. “He said, ‘I hope we worked as hard to be a great dad as we did about working hard to be a coach.’ That was the last thing he said to me. I was early on in coaching and he wanted to make sure I didn’t get my priorities in the wrong place. I try to keep that in mind when we think what we do is so ultra important.”

Rowell put into perspective the mark of Massey’s reach.

“There are a lot of good daddies, husbands, workers and business leaders running around Mobile County because of coach Massey,” he said.

‘Dadgum it!’

When Massey took the Citronelle job in 1982, his wife said it came with a disclaimer: “We were told the two hardest things to be in Citronelle was a Baptist preacher and the football coach,” she said.

Massey didn’t curse, so he had a head start on the preacher part.

“He had a unique way of coaching you hard without cussing you but he’d create words you’d never heard before that made you feel like he was cussing you,” said Sumrall, who said he was an overachieving player when Massey was at Grissom.

Rowell knew to be wary of two trigger phrases when Massey coached the Wildcats.

“If he said ‘Dadgum it!’ or ‘Crap it!’ or ‘Dadgumit, crap it!’ together, you knew he was mad,” said Rowell, who is painstakingly constructing his Citronelle program the way his old coach would have. “That was as bad as it got.”

The football was much worse before Massey came to town in 1982. In the 17 years before his arrival, the Wildcats were 81-84-6 with one region championship; in Massey’s 17 years, they were 108-73-1 with four region championships.

Massey let it be known that Citronelle wasn’t going to take anything off anybody anymore, that the other guys had best go find a cottonmouth to kiss because that would be easier than beating his boys.

“He could take a team that everyone else would say couldn’t win and didn’t have any athletes and find a way to compete and win,” said Ace, who was a good athlete in her own right. “Maybe not win every game but his kids were so tough and they weren’t scared. He taught them how to compete. … He got kids who had no hope and he brought in excitement. You were going to be a better person. He was going to work your tail off and make you better.”

Massey immediately put the Wildcats in position to win games instead of getting routed. His average losing margin in 17 seasons and 63 regular-season games at Citronelle was 11½ points, a one-touchdown improvement over the 17 years preceding him.

In one hapless stretch between 1970 and 1975, the Wildcats were humiliated by losses of, in order, 33, 34, 27, 16, 20, 22, 18, 26, 23, 14, 37, 40, 15, 14, 25, 42, 26, 35, 26, 12, 35, 84, 21, 12, 19, 27, 33, 21, 35, 40, 28, 20, 15, 18 and 20 points. There were also cruel losses of 2, 7 and 9 points.

In one hapless stretch between 1970 and 1975, the Wildcats were humiliated by losses of, in order, 33, 34, 27, 16, 20, 22, 18, 26, 23, 14, 37, 40, 15, 14, 25, 42, 26, 35, 26, 12, 35, 84, 21, 12, 19, 27, 33, 21, 35, 40, 28, 20, 15, 18 and 20 points. There were also cruel losses of 2, 7 and 9 points.

Massey had 10 straight winning seasons and 13 in all; never before or since has any Citronelle coach approached it. By the time he was finished, Massey had a third of the school’s 37 winning seasons.

Those who played for him said Massey could make players perform better than they were.

“He made you believe you could do things you thought you couldn’t,” Rowell said. “I remember times on the sidelines after an offensive turnover, he’d go into the defensive huddle and tell them, ‘If they can take the ball away, well, crap it, we can too!’ It seemed like the defense would come away with a turnover every time he said that.”

Massey didn’t walk on water but could seemingly divert it if needed.

“Many of us thought he had magical powers,” Rowell said. “It would be raining and we would take the practice field thinking this wasn’t gonna last real long. He’d come out and say, ‘It’s a great day to be a Wildcat!’ and it seemed like the rain always stopped.”

Time for a turnaround

The program hasn’t been the same since but the rain might finally be subsiding with the arrival of Rowell, who while he isn’t the second coming of Massey is one of the pine knots he carved, is familiar with the doctrine and applies it. Like Massey, Rowell has been charged with a turnaround and even now, long-dormant seedlings of success, turned over by Rowell’s trowel, are beginning to pop through the soil where oil once gushed.

Rowell has already given Citronelle fans hope, going 6-4 in his first year following a 1-9 finish the season before — an enormous rearrangement never seen at the school. But he downplays the ever-growing feeling, especially since he learned football under Massey, that he is the savior the Wildcats have longed for.

“The players staying where they are and the community rallying around the program is the savior of Citronelle football,” he said. “There were times last year the stadium was full and you saw the sparks of it. I think we can see a special run of football we haven’t seen in some time.”

Those sparks were kindled by Massey. And Rowell, while his own man, is proud to fan them.

“Coach Massey is one of the reasons I wanted to be a head coach and come back here,” said Rowell, who installed a photo of Massey anyone can see upon entering his office.

“I see it every day,” Rowell said. “It’s a reminder there are no short cuts.”

Rowell is living that philosophy. After staying in a camper for 15 months with his wife and three daughters, he built a new house and recently moved in.

“Coach Massey was a humble, hard-working Christian coach,” Rowell said. “If I can be half the man he was as a coach, the X’s and O’s will take care of itself.”

Rowell is not bothered by community pressure to succeed at or beyond Massey’s level.

“There’s no pressure anybody can put on me greater than what I put on myself,” he said. “I’ve been successful everywhere I’ve been. I had a good job at Luverne. This is the desert God called me to.”

Hated to lose

Rowell is trying to return Citronelle to the football oasis it was under Massey, who like all coaches had his idiosyncrasies and protocols.

He loathed earrings unless women wore them.

“Two of our better players came in with earrings for summer workouts and he wouldn’t allow it,” said Rotch Dungan, who was given his first coaching job by Massey at Citronelle, stayed for 14 years and now coaches for Kelly at Saraland.

“Two of our better players came in with earrings for summer workouts and he wouldn’t allow it,” said Rotch Dungan, who was given his first coaching job by Massey at Citronelle, stayed for 14 years and now coaches for Kelly at Saraland.

Massey’s coaches were not allowed to chew tobacco on the field, not even in summer workouts.

He was a devoted family man who saw his daughter Katie born just before a kickoff in 1982, then raced back to the field by halftime.

“Katie always said, ‘I can’t believe he left! I’d be mad at my husband if he had left,’” Ace said. “I didn’t get mad.”

He was genteel by nature but upbraided Rowell for making a C in freshman algebra class.

“It was one of the worst paddlings I ever got,” Rowell recalled. “That was truly the board of education. He set the same high standards for you off the field.”

He wouldn’t tolerate his players fighting during a game — which had been somewhat of a Citronelle tradition — yet the team got involved in a brawl at a Mobile bowling alley when Massey and his players came to Ace’s defense against two patrons.

With the coach bloodied and back on the bus, Ace heard the driver say: “Coach Massey, this is OK. These boys would rather have a good fight on a Friday night than bowl.”

He was a workaholic who taught football, algebra and Sunday school and watched film incessantly, even at home, yet gave his coaches Saturdays off so they could spend time with their families.

He always displayed sportsmanship, yet detested losing.

“He grew a lot in his temperament,” said Ace, who recalled Massey’s reaction to Livingston’s lone loss in the 1971 national championship season, a 21-20 defeat to Troy in which he fumbled.

“When they got home, he got out on the field and was running bleachers at midnight,” she said. “Coach Andrews had to come get him off the field.”

Years later, as a coach, he went into the night after a galling loss to an inferior team, showing he could still be intransigent about certain defeats.

“He was pretty upset,” said Rowell, who was a waterboy/manager and not at all like the incorrigible cartoon characters of his youth. “After the game, nobody could find coach Massey. He left his truck at the fieldhouse and walked home. Or maybe he ran. It burned him so bad because he was such a competitor but he competed the right way.”

The aura of Massey

Doing things the right way is a common refrain among those who knew Massey and it left a positive imprint beyond the field.

Massey coached 14 All-State players at Citronelle, six at Thomasville and 13 at Grissom, including Tennessee star Jayson Swain and Sumrall, along with hundreds of others who are still living with Massey’s aura draped over them the way you’d pull on a raincoat in a squall. Massey infused his players with the expectation of success.

“When he got to a school, you couldn’t help but be excited,” Ace said. “He would tell them, ‘We’re going to win.’ He’d make the kids think they were going to win everything. When you talk to those kids in Citronelle, they talk about the spirit in that school when he was there. He taught them to do right.”

And Massey did right by his players, including the Wildcats’ Travell Reed, who died of a brain tumor.

“Travell told Ronny, ‘Coach, I just want to live long enough to walk across the stage with my letterman’s jacket on and my diploma,’” Ace recalled. “On graduation day, Ronny pushed him across the stage in a wheelchair with his letterman’s jacket on and his gown underneath. Ronny took him out to the car, picked him up in his arms and put him in. Two weeks later, he died. Ronny spoke at his funeral. Those kids know he loved them so much.”

Massey started showing that love even before they were his players. While he didn’t know it at the time, he trained one boy in particular to be a future coach.

Massey, who lived on the same street, started picking up a 10-year-old Rowell early in the morning and took him to the fieldhouse.

“This went on for two or three summers,” Rowell said. “I’d go and mop and sweep and cut grass. My parents thought it was free babysitting. Coach Massey showed me the value of hard work. It wasn’t all X’s and O’s. I’d sort papers for him. He had the eligibility papers in a three-ring binder. You did it all by hand then. I saw a lot of things kids didn’t get to see.”

They’d often go to lunch at Ward’s, usually ordering a hamburger or chili cheeseburger.

All the time Massey invested in Rowell paid off when he turned a defensive end into ground chuck as a freshman.

“It was the first time he got excited about me as a player,” Rowell said. “We were playing Escambia County and we ran a trap right and I was the left guard. I just flat-backed the defensive end, just demolished him. Maybe it was because he didn’t see me coming but the next week I dressed out with the varsity.”

Coached to the end

Ace said her husband would still be coaching today at the age of 74 because of his passion for the sport but, unfortunately, Massey died of a rare cancer at the age of 60 in Huntsville on Aug. 17, 2010. In addition to his wife and daughter Katie, who is a Ph.D. living in Colorado, he also left behind his son Matt, who is now the president of the Alabama School of Cyber Technology and Engineering in Huntsville, and eight siblings, including his brother Larry, who was also a football coach and the father of Leroy state championship coach Jason Massey.

Ronny Massey, who had taken the head coach’s job at Richland (Tenn.), began experiencing intense back pain, had night sweats and lost weight but for months his bloodwork showed no signs of the insidious carcinoma of unknown primary origin.

“He never took an aspirin in 38 years of marriage,” Ace said. “He was so tough, he didn’t complain. He had back surgery. The doctor came out and told me the cancer was all in his femur bone. He said he had tiny little tumors throughout his body. By the time it was detected, it was too late.”

In the spring of 2010, still unaware he had cancer, Massey took the Richland job. Even after the diagnosis in June, he coached until his ravaged body could not go on, a last measure of doing things the right way, of living out his affection and dedication to the game.

Jason Massey, who has won two state championships at Leroy, expected nothing less.

“I grew up listening to him and my dad,” Massey said. “At some point and time at any family function, they’d be sitting at a table drawing up X’s and O’s on a napkin and talking football. … He had total commitment. I knew he’d never be able to give it up. He coached to the end.”

Courtesy of Call News.