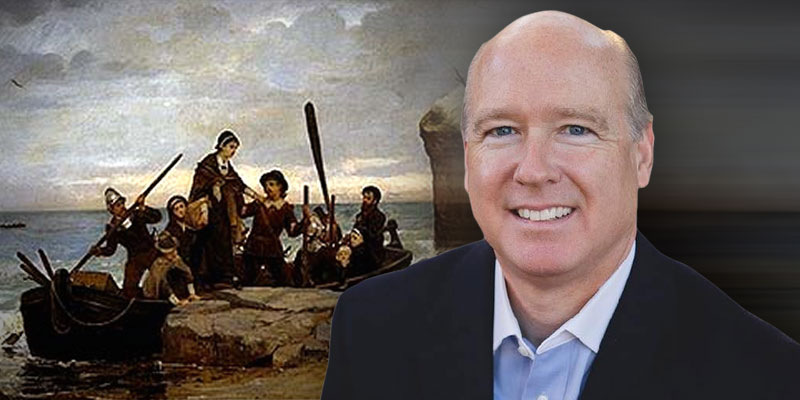

Four hundred years ago this month, a group of just over 100 people arrived off the shores of Cape Cod after a two-month sail from England. They were dissenters from the Church of England like the Puritans but went further by formally separating from the established church they considered to be corrupt beyond repair. We call them “Pilgrims,” although there is only one instance when any one of them used that word to describe themselves. That person was William Bradford, the longtime governor of the Plymouth Colony, who borrowed the word from the 11th Chapter of the Book of Hebrews.

Their arrival that November was not the occasion of the first Thanksgiving. That came the next year when they had built their homes and brought in their first harvest. In fact, they spent their first few months in a harsh winter still on their ship, the Mayflower, while their settlement was built.

Their original destination wasn’t Plymouth but the mouth of the Hudson River where New York City is today, then the northern part of the Virginia Colony, but they were weary after a long journey, running low on provisions and determined to begin the long work of establishing their new home. That meant they weren’t on land covered by Virginia’s royal charter and so there were no colonial government or laws. Some on the ship weren’t separatists like the Pilgrims, remaining true to the Church of England, and talked about “using their own liberty.” These “Strangers,” as the Pilgrims called them, thus threatened the order of the new community.

So, before they landed, all of the adult male settlers on the ships, Pilgrim and stranger, reached an agreement we know as the Mayflower Compact under which they organized themselves as a “Civil Body Politic” by which they could “frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices from time to time, as shall be thought meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony.” They weren’t declaring independence from England but laid out a basis for people to govern themselves in America. Their example was an inspiration for those who 150 years later would indeed seek independence to form a new American nation with a government based on the consent of the people.

The Compact was also firmly based on the settlers’ religious beliefs. It begins with the words “In the Name of God, Amen”, and states frankly that their voyage to America was “undertaken for the Glory of God, and the Advancement of the Christian Faith.” Yet, as they differed on exactly what their faith meant, they established not a theocracy but a civil government based on the laws made by the settlers themselves. Their settlement was risky, and their path filled with hard work, privation and danger, but their faith sustained them. That faith would indeed inspire them to hold a three-day time of thanksgiving a year later after a successful harvest.

Perhaps, in this time of political polarization, we should renew our compact with each other as members of a great nation. Understanding our differences, we can yet agree to work with each other through those differences and achieve a successful consensus based upon shared principles and the value of sacrifice and hard work. As President Lincoln observed, we are the last best hope of earth, a nation founded by and beholden to the people. We should, in the words of the Declaration of Independence, “pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.” In the name of God, Amen.

U.S. Rep. Bradley Byrne is a Republican from Fairhope.