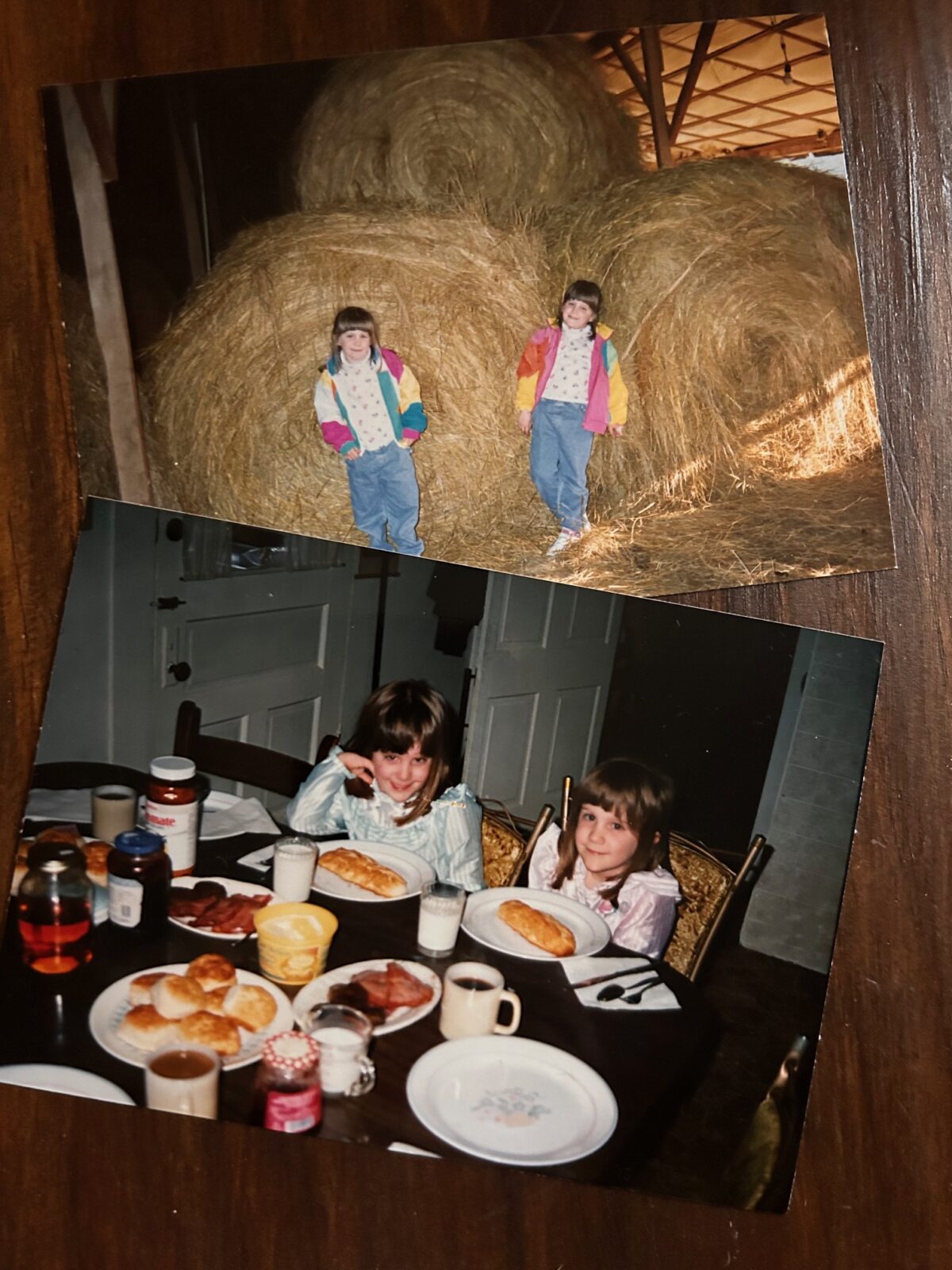

One of my earliest connections to Southern food was in my great-grandmother’s kitchen, on a chicken farm in rural Alabama.

We’d make the drive up from Birmingham and arrive in time for breakfast. My great-grandmother, who we lovingly called Ma Cash, was usually still elbow deep in White Lily flour.

We’d open the screen door and she would be standing over her wooden biscuit bowl, hunched back, carefully turning out each dough ball onto a baking sheet, like little powdered jewels. “Come here and let me dust your britches!” she’d exclaim with a toothy smile.

To this day, I still don’t understand what “dust your britches” means, except that we would embrace and she’d give my sister and me a few pats on the rear, usually while chattering about how tall we’d gotten in her thick Southern accent.

There’s still nothing in this world that tastes better than those mornings at Ma Cash’s house. Once the biscuits were whisked out of the oven, we’d crowd around the table — a rickety card table with plastic-covered chairs — and sit down to feast.

Breakfast was always deceivingly simple: coffee, a few slices of country ham, and the soft, pillowy biscuits, piled high with butter and Golden Eagle syrup.

We’d take our time, catching Ma Cash up on school news and violin lessons and new friends, to the sound of clanging forks and the metal chair legs occasionally screeching on the vinyl floor. On those mornings in North Alabama, time didn’t exist — it simply rested.

Looking back now, I can clearly see how my culinary education was being formed — not in fine-dining restaurants or in tasting menus, but with steady, unrushed care. It grew from those floured hands, that old wooden bread bowl; it was, and is, deeply rooted in tradition, simplicity, and comfort.

Many years later, I wandered down Rue Saint-Hughes, tattered map in hand, relieved to find the right restaurant for our student orientation dinner. “Chez Mémé Paulette” was no larger than a living room, and dimly lit with a random assortment of dripping candles and sconces.

Warm and comforting, trinkets and tchotchkes hung on every wall — fading paintings, copper molds, vases of dried flowers, the air swelling and thick with the heat from the kitchen.

French and English alike spilled out of our mouths over classes of Côte du Rhone and bites of baguette. Someone noted how baguettes — a real French baguette, a baguette tradition — are by law made with only four ingredients: flour, water, yeast, and salt.

I twirled a slice at eye-level, carefully turning it back and forth, studying its texture. The combination of its crisp exterior and soft, chewy interior made a perfect bite after a sip of wine, warm with blackberry and cloves.

Time slipped away. The restaurant’s specialty, les petites cocottes gratinées, arrived out of the kitchen in enamel-glazed pots. We dipped our spoons in and heaped out bites of steaming potatoes, chunks of ham, and shiny strings of emmental.

The entire restaurant smelled like butter and comfort and warmth. Our chairs were so tightly packed around the table that our shoulders nearly touched as we cheerfully bonded over our love of French language and culture, eager to practice our conversation.

We’d arrived that evening as strangers, from all parts of the world — Korea, Germany, Canada. But that evening we were held together by a sort of magic, a spell of sorts, if spells could be made with ingredients as simple as these. Regardless, that evening felt strangely familiar.

At first glance, these meals come from opposite realms — what could Alabama and France possibly have in common? By age 16, I was fully entranced by the French language and culture — a Southern girl who grew up in a modest one-story, shy, reserved. But I knew what I loved, and I sure as hell loved France.

It perplexed my parents, my friends, but my fascination grew until I declared French as my major in college (much to the chagrin of my dad, who had failed college French twice). The South was my first love, but France had utterly and irrevocably captivated me. It tasted like the best dream — because in a way, it was both new and a memory.

A reverence for simple ingredients. A connection to the land. How both meals move through time at the same pace — slowly, unrushed. And finally, the joy of hospitality.

There’s a feeling that’s difficult to put into words, but it’s one that I continue to chase. When you’re seated at a table, gathered with loved ones, glasses clinking, soft laughter, and bites of simple food cooked with love — these are the moments we live for, the ones I still chase today, whether at home in Birmingham or across the Atlantic.

We lost Ma Cash many years ago, but her joyful spirit, and her ability to gather us around a table, lived on through these new moments in France. I can picture her smile, if she were to see me today — bilingual, well-traveled. As a fiercely strong woman who lived through the Great Depression, she might laugh and remark that I’ve become “fancy.”

And then, she’d still dust my britches.

Courtesy of SoulGrown Alabama