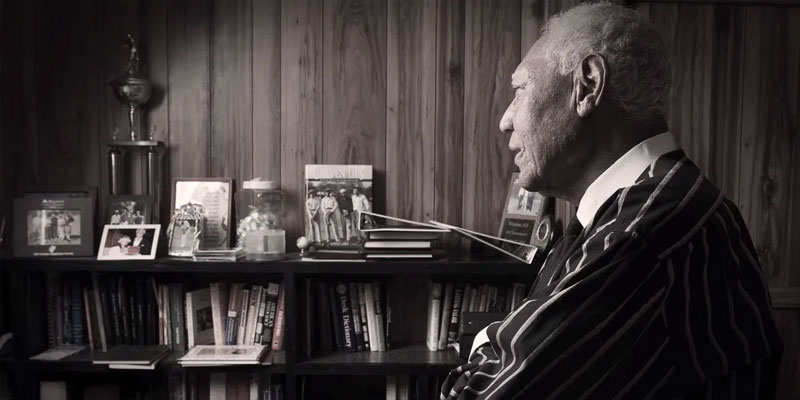

Jesse J. Lewis Sr. has lived almost a century of history and, along the way, made some of his own.

Born Jan. 3, 1925, Lewis last month celebrated his 96th birthday. He grew up in the Great Depression, dropped out of high school, served under Gen. George Patton in World War II, suffered through the racial hatred of Jim Crow and the civil rights era, became a serial entrepreneur, earned five academic degrees, served in the cabinet of one of Alabama’s most controversial politicians, spent a decade as a college president and this past year witnessed a deadly pandemic unlike anything he has seen while watching the social justice movement unfold.

Across 11 decades, Lewis has learned many life lessons, which he shared in his book “One Man’s Opinion: Together We Can Do This,” published in 2020. Lewis sat down recently with Alabama Power CEO Mark Crosswhite for a conversation on legacy, lessons learned, the events of 2020 and how people can work together toward a brighter future.

Alabama Power CEO Mark Crosswhite chats with Birmingham business and community legend Jesse Lewis Sr. from Alabama NewsCenter on Vimeo.

Lewis said he wrote the book “primarily for young Blacks” to help them understand how to succeed in life. The book emphasizes education, entrepreneurship and the power – and necessity – of voting as Lewis shares his life story and what he has learned along the way.

As Crosswhite said of the book, “Your intended audience may have been young Black people, but I will tell you there are lessons in the book for people of every color. … It is a book of optimism and hope, and some tough talk and straight talk, and I know that’s what you intended it to be.”

Lewis’ story begins in Northport, Alabama, where his grandmother Sarah Davis raised him and four of his younger cousins in a small shotgun house.

“I was the oldest, and the bad thing about being the oldest, you’re the one who has to bring some money home to feed the other children,” Lewis said. “All these kids didn’t have no father. We learned how to make a living. It was the responsibility of everybody to bring home a little piece of money every day. That’s one of my great assets.”

He developed that asset cutting grass, selling pies his grandmother made and helping run a laundry business. Lewis honed his entrepreneurial skills in the Army, which he joined during World War II. He was a high school dropout and just 16 years old. “If you were a person of color and you walked up … they didn’t ask you nothing,” he said.

Lewis sent “every penny” of his pay to his grandmother. He did laundry for other soldiers and sold them candy and other items so he’d have some spending money.

His commanding officer was from Auburn and appointed Lewis battalion supply sergeant. The battalion built bridges and it was Lewis’ job to make sure the soldiers had the supplies they needed.

“They didn’t know I didn’t have any education. I had just finished the 10th grade,” he said.

What Lewis figured out is that when given the opportunity to hire a dozen soldiers from the battalion to keep the supplies going, “I picked out the smartest ones in the group. I was the dumbest in the group.” Lewis said the battalion “won every award for two years on having the best run battalion in the 183rd Engineers.”

After the war, Lewis used the GI Bill to get an education. In 1954, after he graduated from Booker T. Washington Business College in Birmingham, he created Jesse J. Lewis & Associates. The company was one of the nation’s first Black-owned PR firms and now operates as Agency54, a full-service marketing and advertising agency.

When Lewis was a student at Miles College in Birmingham and working at the school newspaper, he called Alabama Gov. George Wallace and asked him for an interview. Wallace, a staunch segregationist, agreed.

“I was the head of the publication and my dream was to interview George Wallace,” Lewis told Crosswhite. “I asked him, I said, ‘Governor, are you a racist?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ That shocked me. … He said, ‘Yes, I am. I wasn’t born one, nobody is born one, but I was trained by my grandfather and my father. They trained me to be a racist, but I’m not training my children to be racists. And in addition to that, I’m not going to die a racist.’”

In 1964, just after the height of the civil rights struggle in Birmingham, Lewis founded The Birmingham Times, as he put it in his book, “because there was no voice within the Black community to speak for it.” While Lewis no longer owns the newspaper, it continues to publish weekly. He is its publisher emeritus and still contributes an occasional column.

After Lewis’ interview with Wallace, the pair forged an unlikely friendship that led to Lewis working on Wallace’s 1968 independent campaign for president. Lewis says of Wallace being paralyzed from shots fired by Arthur Bremer during Wallace’s 1972 campaign for president: “My guess would be if he had not gotten shot he would be president.

“Gov. Wallace was one of the best politicians I’ve ever seen in my lifetime,” Lewis said. “He just had the knack of saying the right thing at the right time. He was one of my favorite persons out of all the people I know.”

Lewis said he was asked once about running for public office and he strongly considered doing it – until his wife, Helen, “told me she wouldn’t vote for me. I said if your wife is telling you she won’t vote for you, you’re not a politician.”

In 1975, Wallace appointed Lewis to be the state’s director of Traffic Safety, becoming the first Black since Reconstruction to serve in an Alabama governor’s cabinet. Lewis drew criticism from many Blacks at the time for going to work for Wallace.

In 1978, the state Board of Education appointed Lewis president of Lawson State Technical College, a position he held until 1987.

Through the decades, Lewis continued to create businesses. He established the Lewis Group, a public policy consulting firm, in 1995 while Jesse J. Lewis & Associates continued operations as Elements Communications. Lewis merged Elements with the Lewis Group in 2013. The firm rebranded as Agency54 in 2016, and Lewis continues as its chairman.

This past year, more than six decades after Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus sparked the modern civil rights era, a series of deaths of unarmed Blacks – several at the hands of police – triggered a social justice movement across the United States. Crosswhite asked Lewis to compare the two movements.

“The only comparison you could make, once upon a time Alabama was classified as one of the worst states in the world as it relates to treatment of Blacks,” Lewis said. “That’s not true today. … I can see the progress. I can feel the progress.

“It’s not where it should be, but as my grandmother said, ‘Be going in the right direction.’ We’re moving in the right direction,” he said.

Even before the social justice movement swept across America this past summer, the country had confronted, and continues to confront, COVID-19. More than 441,000 Americans (including about 7,700 Alabamians) have died as of Feb. 1, according to Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resources Center tracking.

Lewis, ever the optimist, believes the pandemic will make Americans a stronger people.

“You’re going to come out with some better people. You’re going to come out with people having more sensitivity to one another. They’re helping one another more and more and more,” he said. “It’s not going to end today, but I’m going to guarantee when this thing is over … you’re going to have people pulling together more than they ever have before.”

During Black History Month, Alabama NewsCenter is celebrating the culture and contributions of those who have shaped our state and those working to elevate Alabama today. Visit AlabamaNewsCenter.com throughout the month for stories of Alabamians past and present.

(Courtesy of Alabama NewsCenter)