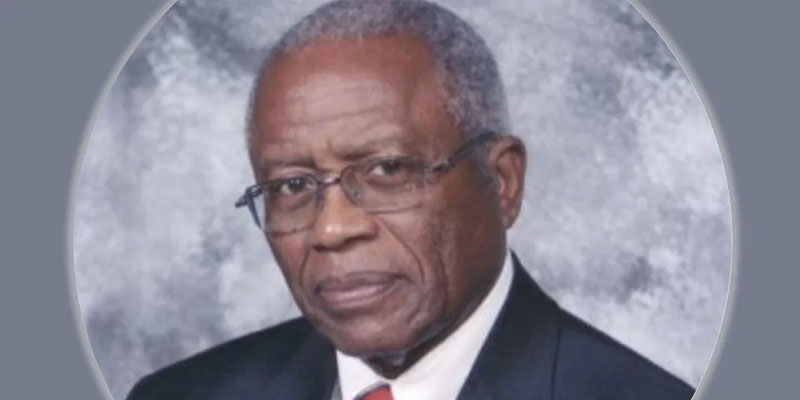

Few people can say they knew Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks when that internationally celebrated pair were average citizens.

Fred Gray can.

The 90-year-old legendary civil rights lawyer has known most of the most-respected figures in the modern movement toward equality for Blacks. He represented Parks and King, persuading judges to make rulings that helped shape both of their lives. Gray’s courtroom victories led to many of the most important gains in reducing the vast disparity in rights that was a reality in America when he opened his first law office in Montgomery.

“Fred Gray is truly one of the giants of not only the legal profession, but of American history,” said Patricia Lee Refo, president of the 400,000-member American Bar Association. “He is the quintessential example of the great social good which a lawyer can accomplish.”

In 1954, Parks helped Gray set up his small headquarters at 113 Monroe St. and within a year he became friends with King. Together, the trio were in the front row of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which in 1956 brought a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that abolished segregation on public buses. Four years later, Gray convinced an all-white jury to acquit King on trumped-up tax evasion charges.

Over the next decades, Gray would win cases that affirmed the one person, one vote principle; ensured protection for marchers from Selma to Montgomery; integrated the University of Alabama, Auburn University and all Alabama public educational institutions; brought equal rights and protections to college students; ended systematic exclusion of Blacks from juries; integrated public parks; and allowed the NAACP to operate in the state. King called Gray “the chief counsel for the protest movement.”

“He’s one of my heroes,” said Pulitzer Prize-nominated historian Wayne Flynt. “I got to know him pretty well when I was writing ‘Alabama in the Twentieth Century,’ and I interviewed him, and I really, really admire him.”

Flynt said Gray was never intimidated in the courtroom facing white lawyers, judges and witnesses during civil rights cases. Despite efforts by whites to embarrass Gray, the Montgomery attorney “in an age of apartheid had more bone in his little finger than almost anyone I’ve ever known in their entire backbone,” Flynt said.

“His attitude was not to confront you in the sense that most whites understand,” said Flynt, Auburn University professor emeritus of history. “He was not going to raise his voice and he was not going to fling out profanities and he was not going to stomp his foot but what he was going to do is demand that you respect him as your equal.”

Gray remains sharp as a tack, continuing to work as an attorney for the 67th consecutive year, going into his Tuskegee office each day and tackling cases as if he were beginning his career. He doesn’t seek clients but is constantly asked to provide legal expertise. He hasn’t had a vacation in years, unless one counts when he was keynote speaker at conventions in places where people vacation.

Setting out as a 24-year-old to “destroy everything segregated I could find,” Gray, by most any measuring stick, has accomplished his lifelong goal. Yet, he admits, the road to freedom for Black Americans is still far from being a freeway.

“I think that we’ve made a tremendous amount of progress in almost every aspect of American life,” Gray said. “I’ve been able, with a lot of help along the way, to be instrumental to do some of that. However, the struggle for equal justice continues.”

Gray said he was alarmed at incidents that fueled the Black Lives Matter movement of the past year. His concerns were amplified by the “mob that went up to the Capitol” on Jan. 6. He said the nation has made obvious progress since Blacks were brought in chains to America 400 years ago but that two major problems remain.

“Racism is not over; we don’t live on a level playing field,” he said. “Secondly, inequality still exists. I don’t care what aspect you take, whether it’s in housing, whether it’s in employment, or whether it’s in health care or even the distribution of resources, they are not equal. … This country, up until now, has never faced the racism and the inequality questions. We just haven’t faced it.”

Born Dec. 13, 1930, one year into the Great Depression, it didn’t take Gray long to realize his predicament as a Black person on the poor side of Montgomery. His father, Abraham, died when Gray was 2, leaving Nancy Gray with five children and little income. His mother’s formal education ended after the fifth or sixth grade, but she relied on a religious upbringing to cope. She worked as a “domestic” in the homes of white people. Growing up on West Jeff Davis Avenue, Gray knew nothing about the legal profession.

“When I was coming along as a child in the ’30s and the early ’40s, there were only about two professions that Black young men or boys on my side of town could do that were respectable positions; that would be a preacher or a teacher,” he said. “And I decided that I would be both.”

The Grays regularly attended Holt Street Church of Christ, which was two blocks from where Rosa Parks lived and in the same area where the bus boycott began. Fred Gray “used to baptize cats and dogs” in his neighborhood, which caught the attention of his preacher, Sutton Johnson. The Holt Street religious leader recommended to Mrs. Gray that 12-year-old Fred be enrolled in the National Christian Institute boarding school in Nashville, Tennessee. Gray would become a favorite of the school president, Marshall Keeble, who was a pioneer Black preacher nationally in the Church of Christ.

“I was actually pretty good at preaching, because he took me around at that early age … to all these churches in Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and we would preach and we would end up recruiting students,” Gray said.

He graduated in 1948, returned to Montgomery and enrolled at Alabama State College for Negroes to become a teacher. Gray’s family had no car and, because his mother’s home was on the west side of town, he had to take city buses to classes at the college that is now Alabama State University on the east side of town.

“I found out then that Black people in Montgomery had some serious problems,” Gray said. “One, they were being mistreated on the buses, being told to get up and give white people their seats. A Black man had been killed on one of the buses. I concluded that while I didn’t know anything about lawyers, and didn’t know any lawyers, I understood that lawyers help people solve problems, and I thought Black people in Montgomery had problems. … Everything was completely segregated and we were just mistreated in every aspect of life.”

Gray graduated from ASU in 1951, deciding he wanted to be a preacher, teacher and lawyer. Because Blacks weren’t allowed to attend law schools in Alabama, he applied for and was admitted to Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. It was the first time he had ever lived in a white environment. In 1954, he graduated and took the Ohio bar exam, then came home and took the Alabama bar exam, passing both. On Sept. 7, 1954, Gray was licensed to practice in Alabama, becoming one of a handful of Black lawyers in the state.

Gray had been supported in his law school efforts by Parks, ASU professor J.E. Pierce, Montgomery civil rights activist E.D. Nixon and others. He’d followed his mother’s instructions to “Keep Christ first in your life, stay in school, get a good education and stay out of trouble.” She’d told him it was fine to be a lawyer, but to never stop preaching. Gray would preach at Newtown Church of Christ in the midst of important early civil rights trials and he continues preaching today.

Even before the bus boycotts, Gray was being groomed for that historic stage. He’d hardly begun practicing when he was hired to represent 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, who’d been arrested on March 2, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat to a white person on a Montgomery city bus.

“That was my first civil rights case, before Judge (Wiley) Hill. And I tried to explain to Judge Hill that she was not a delinquent … but they were trying to enforce the segregation laws, and they were unconstitutional, but the judge didn’t listen to me,” Gray said laughing. “He was nice and respectful but he found her to be a delinquent and placed her on unsupervised probation, which meant that she didn’t have to report to anybody. She didn’t get involved in any more trouble.”

Parks and Gray had been having lunch together in his office, which was just down the street from where she worked as a seamstress for the Montgomery Fair department store. They talked for a year about the buses, desegregation, fairness in society for Blacks and what needed to be done to overcome those problems.

“I knew that, though she never told me what she would do, I felt confident that she would not get up and give her seat if the situation arose,” Gray said.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Parks did not give up her seat.

Fifteen years later, Gray and Thomas Reed became the first Black members of the Alabama House of Representatives since Reconstruction. In 1970, Gray would become noted for his legislative expertise and oratory, but four years earlier he had been set to make history alone, prior to some last-minute vote-counting.

“It came out that I was elected (in 1966),” Gray said, “and then down in Barbour County, when the absentee votes came in, I had lost by the amount of votes that I had originally won by.”

After the loss, Gray decided to move from Montgomery to Black-majority Tuskegee, where he set up a law office and was elected to the state governing body. Soon afterward, he learned of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and began representing the victims of the government effort in which Black men were offered free health care without being told they suffered from the disease. Gray won a lengthy court battle for the victims, which ultimately led to a public apology from President Bill Clinton. Gray wrote about his experiences in “The Tuskegee Syphilis Study” and his autobiography “Bus Ride to Justice.”

In his career, Gray has been lauded nationwide, including honorary doctorates from more than 10 universities. He was the first Black president of the Alabama Bar Association. He is in the National Black College Alumni Hall of Fame. He received the American Bar Association’s Thurgood Marshall Award. He was the National Bar Association president in 1985 and a decade later inducted into its Hall of Fame. Gray was named in 2019 as a “Living Legend” by the National Black Caucus of State Legislators and also as an Alabama Humanities Foundation Fellow.

Throughout his eight decades as a preacher, teacher and lawyer, Gray has credited his success to the earliest influence instilled by his mother.

“The Lord has played a major role in all of it,” he said. “I wouldn’t handle a case that I didn’t think the Lord would be pleased with what I was doing. Because I had, first, to be sure that what I’m doing is not contrary to God’s law and, secondly, it’s not contrary to my own basic religious background. So, it played a major role in all of it.”

Gray’s legal work and courtroom battles will be his legacy. He recognizes his role in societal changes since the 1950s has benefited Americans but Gray longs for more to be done in the nation he reveres.

“We need to, one, acknowledge the fact that racism and inequality is wrong, and that needs to start at the top. I’m glad the president (Biden) has taken a step in that direction,” Gray said. “But it also needs to go from the Supreme Court, the CEOs, the heads of our educational institutions, the heads of our fraternities and our sororities and the heads of our religious organizations.

“We have to acknowledge that racism and inequality is wrong,” Gray added. “We have to come up with a plan … and while we talk about it starting at the top, we must also, every one of us individually, needs to realize that racism and inequality is so ingrained in this nation.”

Over his career, Gray has handled thousands of lawsuits. Legal precedent finds his name alongside some of the most important cases in Alabama and American history. Cuba Gooding Jr. portrayed him in the movie “Selma,” persuading federal Judge Frank Johnson to allow King and others to march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. It was a milestone decision, yet legal experts and historians often debate about which of Gray’s cases is most important.

“When a person comes to a lawyer’s office, they usually have a problem,” Gray said. “And they don’t care how many cases you won or lost, all they want you to do is to devote effort to him and his case and get him the results he thinks he’s entitled to, whether he is legally entitled to it or not. I think all of my cases are the most important case I’ve had.

During Black History Month, Alabama NewsCenter is celebrating the culture and contributions of those who have shaped our state and those working to elevate Alabama today. Visit AlabamaNewsCenter.com throughout the month for stories of Alabamians past and present.

(Courtesy of Alabama NewsCenter)