Roy Stewart Moore was an obscure state judge in Etowah County in 1995 and probably would have stayed that way if not for an assist from an unlikely source — the American Civil Liberties Union.

Moore’s courtroom display of a wooden plaque of the Ten Commandments sparked a complaint by an attorney representing a murder defendant. That attracted the attention of critics who also objected to the judge’s practice of opening court sessions with a prayer. That, in turn, drew the attention of the ACLU.

The local branch of the venerable civil rights organization sent Moore a letter in 1993 threatening to sue if he did not cease the prayers. In typical Moore fashion, he ignored the threat, and the ACLU followed through with its threat in 1995, challenging both the prayers and the Ten Commandments display.

Then-Montgomery County Circuit Judge Charles Price allowed the plaque to remain but ordered Moore to halt the pre-session prayer. In a reaction that would become familiar to Alabamians, Moore vowed to defy the order. Price then issued a new order requiring Moore to take down the plaque, as well.

The Alabama Supreme Court temporarily blocked Price’s order from taking effect and then later dismissed the lawsuit on technical grounds. But by then, Moore was a household name in Alabama and a hero to Christian conservatives. He parlayed that into a successful run for chief justice of the state high court two years later.

ACLU leaders probably would say today that the fight was worth it, that principle demanded a legal challenge to practices they consider unconstitutional. One wonders, however, if that judgment is the same in the privacy of their thoughts.

Without the ACLU and the ensuring national spotlight, there likely would not have been a successful campaign for the Supreme Court — a run aided by Moore’s universal name recognitions in primary and general elections against opponents most voters likely could not have picked out of a lineup.

Moore could not have ignited a controversy over a 5,280-pound granite Ten Commandments monument he erected in the Alabama Judicial Building in Montgomery. No turmoil over his defiance of a federal court order to remove it. No fight to remove him from office. No comeback nine years later, or controversy over the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling legalization of gay marriage and his efforts to undermine that ruling.

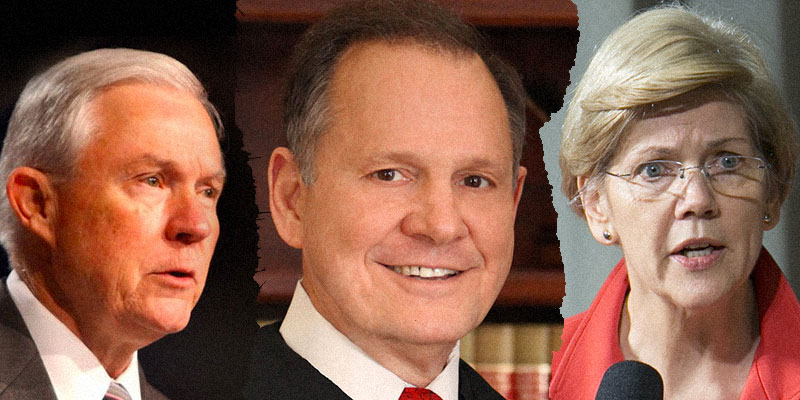

And, of course, Moore almost certainly would not be the Republican nominee for the Senate seat once held by Attorney General Jeff Sessions, dogged by allegations of sexual abuse from nearly four decades ago.

Instead, he may well have been in his final term as a circuit judge — unable to run again because of the state’s mandatory retirement age for judges — a jurist unknown outside of Etowah County.

In effect, the ACLU created Roy Moore.

Jeff Sessions and Ted Kennedy

Moore is far from the only beneficiary of the law of unintended political consequences. The aforementioned Sessions turned the most bitter chapter of his professional life — a humiliating defeat for a federal judgeship in his hometown of Mobile — into a political career culminating with his appointment to his dream job as America’s top law enforcement official.

In that role, he wields enormous power over everything from which crimes to prioritize for federal prosecution to setting drug policy to enforcing civil rights laws, immigration and voting rights.

Progressives vehemently oppose Sessions on almost all of those issues, but in a way, they have only themselves to blame. Perhaps no senator played a more important role in killing Sessions’ judicial nomination than Ted Kennedy, who caricatured the nominee as a racist during the judicial confirmation hearing.

“Mr. Sessions is a throwback to a shameful era which I know both black and white Americans thought was in our past,” he said before casting a “no” vote in the Judiciary Committee in 1986. “It is inconceivable to me that a person of this attitude is qualified to be a U.S. attorney, let alone a U.S. federal judge.”

The Massachusetts senator added that Sessions was “a disgrace to the Justice Department.”

Perhaps the left believes denying Sessions a seat on the federal bench was worth it. But had Kennedy and company just let the nomination go through, Sessions almost certainly never would have run for Alabama attorney general or won a seat in the U.S. Senate. He would not have become President Donald Trump’s most important supporter and adviser. And he would not be setting law enforcement priorities for the nation today.

Maybe at some point Sessions would have won an appointment to an appeals court judgeship. More likely, he would have served out his career in relative anonymity, and at age 70, likely would be a semi-retired “senior” U.S. district judge today.

Elizabeth Warren and Republican obstructionism

Democrats have no monopoly on suffering a backlash after what seemed like a good idea at the time.

When former President Barack Obama was looking for someone to head the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Elizabeth Warren seemed like a natural. Her scholarship had formed the basis of the agency, established by the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010 in response to the financial collapse that triggered the Great Recession.

Obama had appointed Warren assistant to the president and special advisory to the treasury to help set up the bureau.

But Republicans intensely opposed Warren, and Obama never even tried to nominate her. Republicans pressed for changes to the agency before supporting any director.

“We’re waiting for that dialogue, and hope we hear from you,” Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Tuscaloosa) told then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner at a Senate Banking Committee hearing at the time. “Short of that, I think the nominee is not going anywhere.”

Instead of Warren, Republicans ended up with former Ohio Attorney General Richard Cordray as director of the bureau. Based on Cordray’s record, it is hard to imagine conservatives being unhappier with Warren’s tenure had she gotten the job.

Locked out of the position, Warren instead ran for the Senate in her home state of Massachusetts, defeating Republican incumbent Scott Brown. She went on to become a liberal icon, thorn in the side of the Republican agenda and a potential presidential contender.

Had Republicans just let Obama have his original choice to run the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Warren might still be in the job. Cordray, himself, only announced on Wednesday that he would step down.

Who knows? Brown might even still be in the Senate.

Brendan Kirby is senior political reporter at LifeZette.com and a Yellowhammer contributor. He also is the author of “Wicked Mobile.” Follow him on Twitter.