MONTGOMERY, Ala. — The Alabama Education Association (AEA), once indisputably the most powerful force in Alabama politics, has now been relegated to spending almost every dollar it brings in to pay down debt accrued during a disastrous attempt to elect liberal candidates to the Alabama legislature in 2014.

“We’re out of the business,” AEA President Sheila Remington told the Montgomery Advertiser this week. “We’re out of giving people money to run campaigns… as far as people calling and asking us for campaign contributions, I don’t see us getting involved with that anymore.”

According to campaign finance reports filed earlier this week, the AEA has already been spending almost all of its revenue trying to pay down debt. It spent $2.1 of its $2.2 million in 2015 revenue paying off loans. AEA spent a total of $12 million on races in 2014, far more than any other organization in the state.

The traditionally white Alabama Education Association’s rise to power began when it merged with the traditionally black Alabama State Teachers Association in 1969. Paul Hubbert was named executive secretary of the newly-formed group and Joe Reed was named associate executive secretary.

For much of the next four decades, Hubbert was widely considered the most powerful political figure in the state, and he ruled with an iron fist. Hubbert was known for sitting in the gallery overlooking the Legislature and giving hand signals indicating which way he wanted lawmakers to vote on whatever bill was being considered.

But the group’s stranglehold on the state began to loosen in 2010 when Alabama voters elected Republicans to their first legislative majority in 136 years. Hubbert retired in 2011, but the organization he built continued to be a major player in state politics, at least for a period of time.

Here’s how the Fordham Institute described the AEA, which it labeled the most politically active teachers union in the country, in 2012:

Alabama’s union plays a larger role in state politics than do its counterparts in nearly every other state, with contributions from the AEA far outstripping those from any other source. In the past ten years, contributions from teacher unions accounted for 2.8 percent of all donations received by candidates for state office. Those donations also equaled 7.7 percent of the funds from the ten highest giving sectors in the state. Further, 9.7 percent of contributions to Alabama political parties came from teacher unions, the highest proportion we found in any state. These donations represent a key part of the AEA’s political strategy.

Conservatives had long viewed the AEA as the “Dark Side” in Alabama politics, and not only because of its liberal political leanings (both Hubbert and Reed were top officials in the Alabama Democratic Party), but also because the state’s education system continued to rank 49th or 50th year after year, in spite of the AEA’s total control.

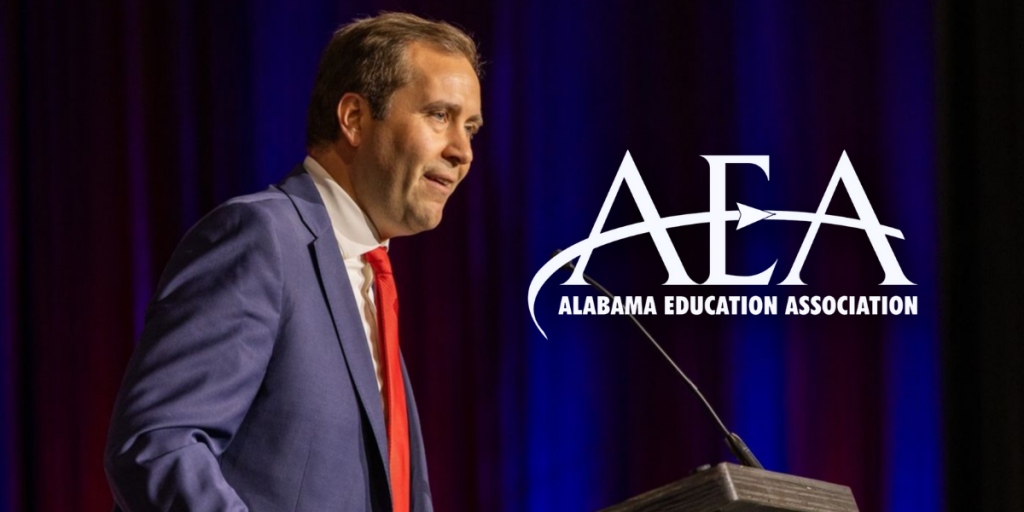

But Hubbert, who passed away in 2014, was considered to be a gentleman, even by his opponents, as well as a savvy operator. However, the Dark Side got its Darth Vader when Dr. Henry Mabry became Hubbert’s successor in 2012.

Under Mabry’s leadership, the AEA’s standing took a sharp nosedive, compelling Hubbert to pen a letter to the AEA Board of Directors urging them to make a course correction.

“With great reluctance, but with absolute conviction of its necessity, I write this letter to you to inform you of the immediate danger, in fact crisis, in which our association finds itself,” Hubbert wrote in September of 2014. “AEA has been a strong organization for many years because of its large membership and its strong financial position. Both of these appear to be under threat now.”

Hubbert said that the problems facing the AEA came from both inside and outside the organization. The external challenges, he believed, were posed by the Republican supermajority in the legislature and the strain on the AEA’s finances brought on by a new law prohibiting them and other politically active organizations from using taxpayer resources to collect membership dues.

But internally, he placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of his successor.

“The style, personality and performance of [Dr. Mabry] have created intolerable friction between AEA and members of both parties in the Legislature with resultant loss of respect, standing and influence,” Hubbert bluntly wrote. “Legislators and others complain that telephone calls are not returned during the session. The Executive Secretary’s style has been described as a ‘bull in a china shop who carries the shop with him wherever he goes.’ The Executive Secretary has been advised to ‘stay out of the Legislature.’ Specific comments and questions from members of the Legislature include, ‘How long is AEA going to keep Mabry?’ to ‘Mabry is killing AEA in the Legislature.’”

On top of that, Hubbert described Mabry as a something like a riverboat gambler, throwing away teachers’ dues in high-risk stock market trades.

“Of specific and serious concern is the expenditure of remaining reserve funds to invest in high risk stock market ventures,” Hubbert wrote. “The demand to participate in highly aggressive stock trades forced Merrill Lynch to refuse to service the remaining AEA investments and the investments were moved to Stern Agee to engage in highly volatile trades. A full audit of these strategies and actions is warranted. High risk trading in the market is no way to use member dues money.”

Mabry was ultimately pushed out, but not before the 2014 election cycle, during which the AEA spent an estimated $20 million of teachers’ money on a disastrous election strategy that resulted in almost no victories for the embattled organization. Their scorched earth tactics included funneling millions of dollars through “dark money” groups that posed as conservatives and spread propaganda against Republican candidates.

As a result, the AEA that Paul Hubbert had spent a lifetime building was completely eviscerated in a single election cycle.

“The AEA’s days are done,” Senate President Pro Tem Del Marsh (R-Anniston) said on election night in 2014. “We want to work with the education community to establish good education policies. We’re committed to that. We want to make sure our teachers are paid well. We want to make sure they have great benefits. But we can do all of that without the AEA union. Their mentality is ‘attack, attack, attack.’ I want to work with our state’s teachers directly, not with the AEA.”

That sentiment is shared by most elected officials around the state, creating an opening for the newly-formed Alabama Unites for Education group to be an advocacy organization that builds consensus, rather than burns bridges, with policymakers.