A remarkable program to help juvenile offenders held its annual luncheon in Mobile yesterday, and the rest of the state should emulate it.

The program is called n.e.s.t., for the first words in the group’s goals to “nurture children, equip parents, strengthen families, and transform communities.” (Henceforth, I’ll call it NEST for the sake of simplicity.)

Founded in 2012 by Mobile County juvenile court judge Edmond G. Naman and acclaimed scholar/minister Norman McCrummen III, NEST uses a volunteer-heavy approach to befriending juvenile offenders and helping them – and often their families – turn their lives around. Rather than trying to stretch itself thin to serve as many youthful lawbreakers as possible, NEST uses multiple volunteers as a team for each offender, providing in-depth assistance at helping offenders do better in school, apply for jobs, and stay out of trouble.

The apparent idea is that it is better to succeed with a relative few, and then grow from there, rather than try a less-focused approach for many offenders and fail to break through. NEST’s results are remarkable.

NEST asked local psychology and clinical mental health professor Tres Stefurak to analyze the progress of offenders with whom NEST worked. Stefurak said the average recidivism rate (within a year) for youth offenders in Alabama is a horrid 66 percent, and nationwide it is around 52 percent. Of NEST-helped offenders, though, the recidivism rate is just 26 percent — and most of those are single recidivists, not multiple re-transgressors.

These are early results, to be sure, and Stefurak says he will continue to track NEST’s progress as it takes on more and more cases. Still, the success rate, even those suffering some very difficult family situations, is quite encouraging.

In his concluding remarks at the luncheon, Naman explained the challenges facing juvenile court. He said its probation officers, whom he called “heroic,” are significantly underpaid. Moreover, just since 2010, the court has lost 50 percent of its staff and 70 percent of its funding. (Please see my piece on Alabama government being underfunded.) He cited the numbers: 91 percent of youthful offenders in his court come from single parent homes. Some 6,000 school-age children in Mobile County are officially homeless.

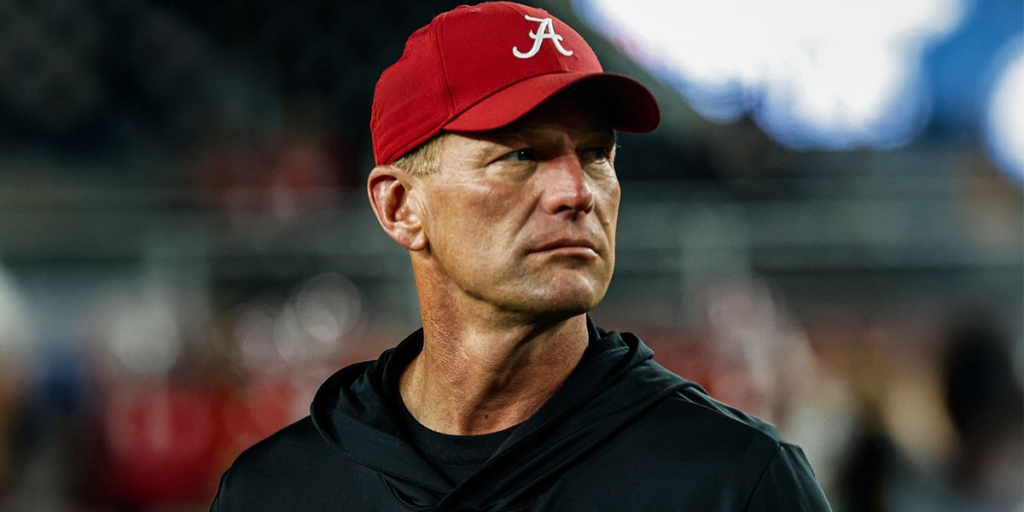

Of one offender, a brawny 6-foot-4, Naman said he looked down from the judicial bench and “I was scared” because of “a deadness in his eyes.” But NEST took on his case. He made it through school and even to college (on a football scholarship), and has stayed on the “straight and narrow.” He even sent a home-made video to the luncheon, thanking NEST for helping turn his life around.

“You saw the video,” Naman said. “There’s no longer deadness in his eyes; instead, you see hope and joy.”

Naman said NEST is successful because it understands the following truth: “A kid can walk around [and thus avoid] trouble if he has someone to walk with and somewhere to walk to.”

Perhaps NEST is a model the rest of Alabama can copy.

Yellowhammer Contributing Editor Quin Hillyer, of Mobile, also is a Contributing Editor for National Review Online, and is the author of Mad Jones, Heretic, a satirical literary novel published in the fall of 2017.